To what extent does the stigma surrounding care-experienced people originate within the care system itself?

- To a large extent (56%, 297 Votes)

- Somewhat (28%, 147 Votes)

- Not very much (11%, 58 Votes)

- Not at all (5%, 28 Votes)

Total Voters: 530

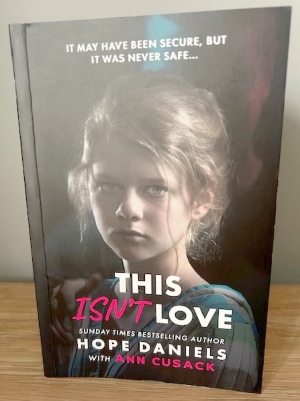

Anyone who has read Hope Daniels’ first book, The Sunday Times bestseller Hackney Child, will know that when she was nine, she walked into Stoke Newington police station with her two younger brothers and asked to be taken into care.

What readers will not know from reading Hackney Child is that Hope was a victim of child sexual exploitation, abuse and rape. This is because Hope herself didn’t realise it at the time.

The publication of Hackney Child led to Hope being invited to talk at events across the country for professionals from social services, police, health and education about being a child in care. And it was, ironically as it turned out, at a safeguarding conference in 2016, that Hope went off script and talked about “an affair” she had had with a married man when she was 14.

The lens of realisation

A police officer approached her afterwards and gently explained that there had been no affair or relationship: she had been groomed, sexually exploited, abused and raped by this man. She was the victim.

In that moment, Hope’s world “jolted and shifted” and “a single atom of the shame and blame which had weighed on me, and bent me double throughout my life, was lifted. From me. To him. This was the start of my healing”.

And so the second part of Hope’s autobiography, This Isn’t Love, retells her childhood through the lens of that realisation.

With a few exceptions – the teacher, social worker, and residential care workers in Hope’s life who showed compassion – this is a story about a care system that spectacularly fails to deliver anything approaching “care”.

It is a care system that makes a girl spend her childhood repeating the mantra: “I am a whore. I am a little slag, I am a slut.”

An uncaring care system

This book made me angry on Hope’s behalf for so many reasons, including at:

- Social workers and teachers who either failed to notice or do anything about what was going on in Hope’s family home. Her parents were alcoholics, neglect was obvious – the children were often hungry and wore dirty clothes. Wherever they lived reeked of urine, sometimes there were rats. Hope’s dad stole a variety of items including food, things for the house and goods which he peddled out of a suitcase at the local market to make money. Hope herself stole food so that she and her brothers could eat. Their mum had stints in prison for soliciting and her dad was convicted twice for living off immoral earnings. Knowing this alone, at the very least, why did it not occur to any professional to question how many bedrooms there were and where Hope’s mother took clients? A walk upstairs would have revealed that Hope slept in her parents’ bedroom and saw everything. The family was moved multiple times, often because of complaints from neighbours. And yet, there were no interventions, as if by moving the family on, the responsibility for what was happening would also be passed on.

- The person responsible for replacing the staff at Hope’s children’s home with no explanation or warning. The children woke up to find a new team in place, denying them the opportunity of saying goodbye to anyone they had become attached to. Yet again, they were given no control over anything in their lives, which left Hope thinking they left because of something she’d done.

- The professionals who not only turned a blind eye but, in some instances, colluded to allow neglect and abuse to continue in children’s homes, secure units, and foster placements. Hope was self-harming by 11, drinking and sniffing aerosols; staff knew but did nothing.

- A system that selected completely unsuitable people to become foster carers and then allowed them to continue when it must have been apparent they were cruel at best, abusive at worst.

- A system that, to this day in some places, gives children bin bags for their possessions when moving between placements. What message does this give?

- The head of the children’s home who told Hope she was disgusting for seducing a married man – when she was 14.

- The construct of secure units – for Hope, these placements were the complete opposite of therapeutic, and to this day traumatised children, young people and adults can be further harmed in such settings. In one secure unit staff encouraged an atmosphere where children fought and then watched rather than intervened – except to physically hurt them under the pretence of restraint. And in another secure unit, a residential youth worker openly sexually abused the girls.

- The fact that some of these people are still working as foster carers and in social care.

- The male doctor who after Hope gave birth to her first baby, didn’t stop to think why a woman would scream at him, “Don’t come near me”. With the pain and drugs, Hope delusionally thought he was the man who groomed and raped her. How many women who have been abused or raped go through childbirth with no thought from professionals about the lack of control and position of vulnerability they are in, lying there with an unknown man over them? All this doctor said to Hope was: “If you don’t settle down, we’ll leave you unstitched. Stay still.”

One of the most heartbreaking stories in this book is when Hope receives an email, not long after Hackney Child is published. It was from the couple that she thought were going to foster her but whom she never met. They were also never told why the placement fell through and were so badly affected that they never reapplied to foster. Hope went to meet them and saw the bedroom that would have been hers.

Adult legacy of childhood trauma

The adult legacy of childhood trauma runs deep. In 2022, to the outside world it looked like Hope was thriving: she was married, had successfully raised two children, had become a grandmother, had a job she loved and had been sober for many years. But a catalyst of events led to her drinking again and then making a serious attempt to end her life.

Fortunately, she was found in time and it finally led to her getting the help she had needed as a child.

It can be no coincidence that the author chose Hope as her pseudonym. Her story ends with hope: she is free from addiction, working and happy. In Hackney Child, Hope feels a lot of anger towards her mum and blames her more than her dad for her childhood.

At the end of This Isn’t Love, Hope has reconciled with her mum after not seeing her for 20 years, and realised that she too was a victim of the care system (as was her dad). After hearing her mum’s story – much of which mirrored Hope’s own – she gradually begins to forgive her and recognises that they are both strong women and survivors.

And so the story comes full circle.

More change needed

Every professional who works with children in care can learn so much from reading This Isn’t Love. It is only because of brave, resourceful, resilient people like Hope that these stories are written. There are signs their voices are being heard, but more change is needed for the care system to live up to its name.

Hope is inspiring and courageous, and so it feels fitting to end this review with her own words from her author’s note at the beginning of the book:

“Since Hackney Child I’ve had a major breakdown and I’ve come to terms with all these issues. I’ve also learned that my mother, whilst she made mistakes, was a victim herself. This book addresses all of this, once and for all. For me, it’s closure; it’s my full stop. There is no more shame, no more secrets. This is my everything. I hope you can enjoy it – it’s a bumpy ride but there is so much light at the end.”

- Jenny Molloy writes under the pseudonym Hope Daniels. To learn more about Jenny’s story and the adult legacy of childhood trauma, you can listen to our Learn on the Go podcast if you subscribe to Community Care Inform Adults or Community Care Inform Children. Or you can subscribe to the series through Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

- This Isn’t Love is published by Mirror Books. ISBN: 9781915306722. £9.99.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Oxfordshire County Council

Oxfordshire County Council  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice

Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice  ‘They don’t have to retell their story’: building long-lasting relationships with children and young people

‘They don’t have to retell their story’: building long-lasting relationships with children and young people  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  How managers are inspiring social workers to progress in their careers

How managers are inspiring social workers to progress in their careers  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

I resonate with this greatly, the impact changes in staff, system and exposition of young people to weird life. The lenses of trauma run deeper than we can imagine and affect individuals’ lives throughout. Wishing if more could be changed. I once wrote an essay on teenage pregnancy experiences among teenagers in care and I was penalised for being emotional but I was just reflecting on true lived experiences and how they impacted my perfection of young people in care.

Thank you ❤️