by Ray Jones

In 2010, a coalition government, led by the Conservatives and involving the Liberal Democrats, came into power.

Taking advantage of, and re-shaping the narrative about, the global economic crash of 2008, created by reckless bankers within deregulated banks, the disingenuous script was that the crash was the consequence of high spending on public services.

Politically-chosen austerity

The administered remedy was a politically-chosen austerity, with cuts targeted towards poor people and public services.

It led to the decimation and fragmentation of the welfare state, the routing of public money to the private sector and increasingly prevalent and intense poverty.

The assumption was that this would drive more people into employment – albeit low paid and insecure within the gig economy. Those who were still claimants of the eroded social security system, including some who were employed, were stigmatised and demonised as a result.

This era of austerity has endured for 14 years now, with pretty awful consequences, including for those who use and work within social care and social work services.

Photo by Ray Jones

At the time, there was a focus on savings. A duo of MPs, one Conservative (Iain Duncan Smith) and one Labour (Graham Allen), also argued the private sector might fund publicly-run services through ‘social impact bonds’, where private investors could pay for a public body to deliver a service and, upon success, the government would repay them with interest.

Continuities with Labour policy

However, it was hard for Labour to argue against the coalition government’s initiatives, because it was the originator of several of them in the 2000s.

It was Labour that introduced academy schools, drawing in private funding and management for schools removed from local authority planning and support.

It was Labour that launched the private finance initiative, using private funding for public sector capital buildings projects, such as hospitals and schools, leaving a legacy of interest and big profits that are still being repaid to private investors.

It was also Labour that introduced ‘social work practices’, under which statutory social services for children and families, disabled adults and older people could be contracted out to the private, voluntary sector or social enterprises.

But in the hands of the Conservative-led government, what were largely marginal projects were brought into the mainstream. For example, the intention now was that all schools should be taken outside of local authorities.

Photo by Ray Jones

Then prime minister David Cameron championed the privatisation of what until then had been public services, while education secretary Michael Gove brought in consultants from big accountancy firms to advise the government instead of public professionals.

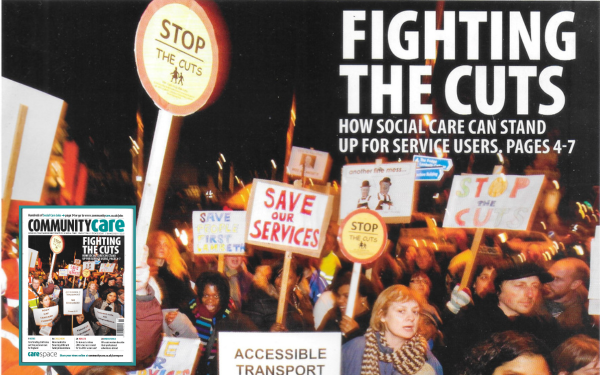

By 2011, as profiled by Community Care, alarm bells were ringing about the potential impact of the cuts in, and commercialisation of, children’s and adult social care services.

More poverty, homelessness and inequality

So, what has happened to those who use or work within social services since 2010?

For children and families and disabled and older people, there have been sustained, increasing and cumulative cuts in social security benefits.

The number of homeless households living in temporary accommodation in England has risen from 49,680 in September 2010 to 117,450 in March 2024. Inequality in life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas in England rose from 9.4 to 9.7 years for men, and from 7.4 to 7.9 years from women, between 2015-17 and 2018-20, according to Office for National Statistics data.

There are also longer waiting lists for health services and big delays within the justice system, while the prices of crucial services, such as water, food, electricity, gas and public transport, have mushroomed.

We are now for many a nation of food banks and holiday hunger, where disabled people are stranded in their own homes.

It is quite amazing what can change in just 14 years through austerity policies.

Cuts to council funding

A particular target has been local authorities, with government funding cut by 55% in real terms between 2010-11 and 2019-20.

Photo by Ray Jones

Despite rises in locally raised council tax, more and more local authorities have declared themselves bust in recent years. Family support services have been eroded, and help for disabled and older people heavily rationed, with higher charges for care. Locally, people are paying much more for much less.

Families struggling amidst increasing stress and poverty get less help due to a perpetual lack of resources, while an increasing number are subject to child protection investigations in the absence of early help. Meanwhile, the number of children in care in England has risen for 15 consecutive years.

A significant number of children taken into care are placed some considerable distance from their families, friends, and social workers into high-cost children’s homes built within decaying communities of low property prices. As of 31 March 2023, 21% of children in care were placed more than 20 miles from home, compared with 15.9% a decade earlier, according to children in care and care leavers charity Become.

For social work, there now exists a less stable workforce, heavily relying on short-term agency social workers. Between 2013 and 2022, vacancy rates in local authority children’s services rose from 14% to 20%, before falling to 18.9% in 2023, according to government statistics. Over the same period, the proportion of agency social workers grew from 12% to 17.8%.

A thriving private sector

But some organisations have thrived. Big companies and international venture capitalists now dominate the provision of children’s residential and foster care. As of March 2024, more than four out of five children’s homes and 86% of independent fostering agencies in England were privately owned, according to Ofsted figures.

And private accountancy and management consultancy firms have been contracted by the government to re-shape social work and social workers’ education. For example, in 2015, KPMG, a multinational professional services network, was contracted to develop a system for assessing and accrediting social workers.

Risk assessment and risk management have trumped relationship building and the provision of help. What social workers do has become more skewed, pressurised and stressful.

Will things change?

A big question now is, after 14 years of politically-chosen austerity, will the tanker be turned, with public services again valued and those who use and work within public services respected and resourced?

For a start, this requires the re-funding of local government, the voluntary sector and community partners, and the reinvestment in locally provided public sector services. Maybe the forthcoming Budget will give a glance of the future direction of travel?

Expect Community Care to track the trajectory and tell the story as it has over the past 50 years.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Oxfordshire County Council

Oxfordshire County Council  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice

Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice  ‘They don’t have to retell their story’: building long-lasting relationships with children and young people

‘They don’t have to retell their story’: building long-lasting relationships with children and young people  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  How managers are inspiring social workers to progress in their careers

How managers are inspiring social workers to progress in their careers  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Excellent article from Ray Jones which should be published in all the mainstream media, not just for readers of community care who already live this daily reality. Many of the disenfranchised have now been led to the idea that all their woes are the fault of asylum seekers seeking safety in this country and it’s terrifying how.far these ideologies can lead us. We can only hope Labour can offer some hope…..(?)